-

Hawking for a Medieval Christmas Feast

8th December 2023

Christmas is a time of feasting and it was no different in history. Although our modern Christmas is largely shaped around Victorian tradition, there are strong echoes of Medieval ritual rooted at its core. Medieval feasts relied heavily on the proceeds of hunting meaning the autumn and winter months were the busiest times in the calendar for huntsmen of all varieties. That included hawkers and falconers. For most of the year any quarry caught would go to the hawk’s larder or be consumed by his master, but in the winter there was a higher purpose – the royal larder.

One of the greatest Christmas feasts staged in British history was that of Henry III at the city of York in 1251. He organised an elaborate banquet to celebrate the marriage of his daughter Margaret to Alexander III of Scotland, it was held on Christmas Day and generated such a comprehensive shopping list that preparations commenced many months in advance. The menu included 830 deer, 200 boar, 1300 hares, 115 cranes, 125 swans, 2100 partridge, 290 pheasants, plus ducks, pigeons, rabbits, fish, eels…the list alarmingly goes on. While some birds and beasts could be bought or harvested from managed domestic stocks, the larger animals were taken by huntsmen from the Royal Forests and the King’s estates and parks. However, the game birds, specialist wildfowl, and hares were generally supplied by the King’s court falconers, hawkers, and fowlers. Apart from providing the monarch with sport whenever he wanted to go hunting, the falconers’ main role during the winter months was to provide fresh game for the kitchens – particularly around Christmas and the New Year. Medieval Kings would often put rivers and waterways rich with game “in defence” during certain periods of the year, prohibiting anyone to hunt in the area. Promises, obligations and favours of hawks and falcons owed to the king would be called in, and servants living in sergeanty tenure in different parts of the realm would be summoned to the royal court. All hands on deck were required!

In the Middle Ages the Goshawk was the everyday practical hunting device used for catching edible birds and mammals for the pot. The man who specialised in hunting with a hawk was known as an “austringer”. The word derives from the old French-Norman word for a hawk “oster”. An austringer had to be physically fit and able to swim in shallow water because his hawk was an athletic sprinter and would often chase quarry over streams and across ponds, the austringer had to be capable of following the flight quickly on foot as hawks would often fly where it was too difficult for a horse to follow. A hawk would be flown in the same way we work them today, on foot from the glove so it could explode into pursuit should the austringer walk up and flush some quarry. A dog might be used or perhaps a strategically placed beater to ensure success. Rather unfairly, austringers were held in lower esteem to falconers, their skills thought to be less exacting and their charges less noble than falcons. In truth it was simply a reflection of the fact that hawking was more solitary, every day, and military in practice compared to the social and rather more staged nature of falcon hunts. The goshawk was provider of two of the most important meats for the banquet table namely pheasant and hare. Modern hawkers catch a lot of rabbit but of course there were no free living or “wild” rabbits in Medieval Britain as they were an imported species housed and farmed in fortified warrens. Wild ducks were also caught but not as highly prized as other quarry because there were farmed equivalents.

Worthy of discussion, the pheasant becomes a tradition at Christmas feasts from the 1100’s onwards – first recorded by the Canons of Waltham Abbey at the feast of King Harold in 1060. The pheasant is not a native bird, it was first introduced by the Romans but disappeared when they withdrew from Britannia and was then introduced a second time by the Normans from Sicily. Those original pheasants were small and dark, they did not survive well in the wild and were mostly reared in aviaries. The pheasant that we recognise today is a descendant of the more recently introduced Chinese ring neck which was brought over in the C18th and has inter-bred so well that most British pheasants now sport a distinctive white collar. Pheasant remains a popular and affordable choice today, but it was a decidedly upper-class meat in Medieval England! Of similar high status, the hare was renowned for being a difficult creature to catch. Its red meat was considered extremely delicate and precious, and its rarity made it expensive, but hare was not impressive or decorative enough to take centre stage at a royal festive feast. The whole carcass could not be easily or attractively presented so it became a rich ingredient in a civet or stew and in potted meats.

Digressing a little but still of relevance, turkey is of course the roast bird of choice today, but the turkey was not introduced to Britain until the C16th. It came from the New World and was first brought to England in the 1540’s when it was presented as a gift to Henry VIII. Goose did not generally make the Christmas banquet table as that delicacy was commonly reserved for Michaelmas, a Christian festival celebrated on 29th September, but because the news of the defeat of the Spanish Armada arrived on Michaelmas Day while Queen Elizabeth I was dining on goose, she decided to elevate its status and add it to the Christmas menu thereafter.

Returning to the hunt, the lordliest of the Medieval hunters were undoubtedly the falconers, those who hunted specifically with falcons. Fierce competition used to exist between hunters (those who chased deer and boar on horseback) and falconers at the French Royal Court. In the spring when the falcons began to moult and could no longer be flown, the huntsmen had the upper hand. On May 3rd the huntsmen all dressed in green would rush into the court sounding their horns and using green twigs to symbolically chase the falconers out. This was the time of the stag hunts which lasted until the 14th September. But once that date arrived, the grey winter-clad falconers would return to the court and send the huntsmen dragging themselves back to their kennels. The winter was the realm of the falconer! Falconry practice has always been driven by the seasons which is why it is commonly represented in Medieval calendars as it was not a year-round activity.

It was believed that the most pleasure could be had from hunting with a falcon, and the most unusual game caught as a result. The open air and highly visible nature of falconry meant it served as an exciting form of outdoor entertainment for the rich and titled, who could follow excitedly on horseback and watch the dynamic chases from below. The by-product was the acquisition of rare and delicate game including unusually large waterfowl. That is why King John had 350 paupers fed in return for his falcons’ capture of 7 cranes on Holy Innocents Day on Dec 28th, his penance for committing the violent sin of hunting on a holy day. It was estimated that an individual falcon could catch between 40 – 60 quarry items per season so all the royal falconers together could make a valuable contribution to the Christmas feast including partridge, snipe, woodcock, duck, pigeon, and pheasant. Not only that, but the falconer would also often provide the table centrepiece, the novelty dressed bird which would sit at the centre of the banquet table and serve as an impressive talking point. A heron or crane whose skin had been carefully stretched over a wire frame to create a lifelike sculpture would sit proudly with its head raised and wings outstretched over the sumptuous feast below. Rather macabre by modern standards but a piece of table theatre in its day, particularly if the king could entertain his guests with the story of its capture! Falconry was time and labour expensive and therefore a very costly way of providing meat, but at least it was rare and delicate meat, so aristocracy thought it worth the effort! Peregrine Falcons shouldered most of the winter work, but Lanners were known to be most excellent for catching partridge, and Gyr Falcons flying as a cast were necessary for the capture of heron and crane. Henry III owned many Gyrs and sent his falconers to Norway to buy them, but he also received and gave away tens of Gyrs as expensive gifts.

The last avian contributor to the Medieval feast was the fowler, a specialist in catching wild birds using many techniques including nets, bird lime, and decoys. Fowling is thought to be the most ancient form of hunting birds and the forefather of hawking and falconry. Ancient Britons were known to use a wild sparrowhawk for fowling, to catch woodland birds using nets after introducing a natural predator to worry them into flight. Later, in Anglo Saxon times, a man hunting with a hawk was referred to as a fowler indicating the infancy of hawking and the fact it had not yet emerged as a separate skill. One common and extremely ancient method of decoying was to use a woodland owl to attract birds, it was a clever way of harnessing a natural process and manipulating nature for human convenience. Aristotle the Ancient observed little birds being drawn to an owl in admiration of its beauty, or at least that was the illusion. In reality, the birds were mobbing the owl through fear, to drive it away before darkness when the silent owl would become a threat, because the owl can navigate in the dark, but the diurnal birds cannot. Any woodland owl caught out in the open during daylight will attract birds and so they became a useful tool for drawing birds out of cover and to a particular spot. A tawny owl is frequently described in history as a good decoy, tethered in the top of a tree on whose branches have been slathered sticky lime so that any birds landing to harry the owl get stuck. On royal hunts it is well documented that Eagle Owls were employed as decoy birds to attract in the larger target species which included, rooks, red kites, herons, and cranes. On this occasion the large owls were tethered to open ground where they were clearly visible for miles. It was undoubtedly a very unhappy task for the unfortunate owl but Medieval man had few morals about such things.

It would be an overreach to suggest that Henry III could not have staged his elaborate Christmas fest without the input of his austringers, falconers and fowlers, but it would certainly have been poorer without their contributions. Many kings kept records of game in their annual hunting rolls and that gives us an idea of who caught what. If nothing else, it consolidated the importance of the royal hunting department and all the hunters employed within, fortunately for them keeping them in service all year round. A falconer or an austringer was not just for Christmas!

Emma Raphael.

References:

The Kings and Their Hawks, R. S. Oggins.

The Great Household in Late Medieval England, Woolgar.

The Sinews of Falconry, G. Robinson.

The History of the Countryside, O. Rackham.

The Art of Medieval Hunting, J. Cummins.

Falconry and Art, De Chamerlat.

Feast, R. Strong. -

The Osprey: A Hunting Bird?

6th April 2021

Long have we explained to people that although the Osprey is a bird of prey, it has never been employed in history as a falconry bird. The main reason is practicality! One cannot easily hunt with a bird which specialises in hunting over water; the bird cannot be followed in flight as one does with a land hawk, and therefore the catch cannot be seized, nor the bird recalled. The only exception is the cormorant, which can be deployed to dive from a boat via a long tether line, and therefore to which it must return. An osprey catches fish with its feet while a cormorant scoops them up in its beak, so the techniques are completely different – rendering one useful and one useless!

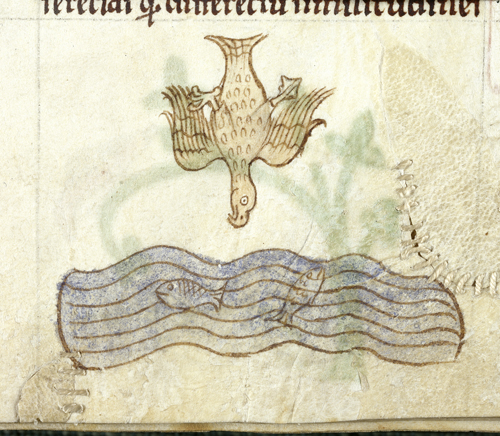

There are various medieval illuminated manuscripts which clearly depict ospreys hunting, they appear in natural history publications describing the flora and fauna of a certain period. It was commonly thought that the Osprey had one hawk-like foot and one flipper or webbed foot, as clearly depicted in the image accompanying this article (from the C13th Topographia Hiberniae). It was not until we stumbled across a reference from 1577 that all became clear and we discovered that Ospreys could be used for catching fish, just not in the conventional way.

“We also have ospreys, which breed with us in parks and woods, whereby the keepers of the same do reap in breeding time no small commodity; for, so soon almost as the young are hatched, they tie them to the butt ends or ground ends of sundry trees, where the old ones, finding them, do never cease to bring fish unto them, which the keepers take and eat from them, and commonly is such as is well fed or not of the worst sort. It hath not been my hap hitherto to see any of these fowl, and partly through mine own negligence,; but I hear that it hath one foot like a hawk, to catch hold withal, and another resembling a goose, wherewith to swim; but, whether it be so or not so, I refer the further search and trial thereof to some other. This nevertheless is certain, that both alive and dead, yea even her very oil, is a deadly terror to such fish as come within the wind of it.”

Description of Elizabethan England by William Harrison.

So in summary, park keepers would shamelessly use osprey chicks to extort large quantities of fish from the diligent parent birds. And the osprey was suspected of exuding a toxic oil which killed fish. Whilst the first statement is likely true, the second most definitely is not! Neither does the Osprey have one webbed foot! An interesting first-hand perspective of a very misunderstood bird.

-

What story does this picture tell? Let's investigate......

26th March 2021

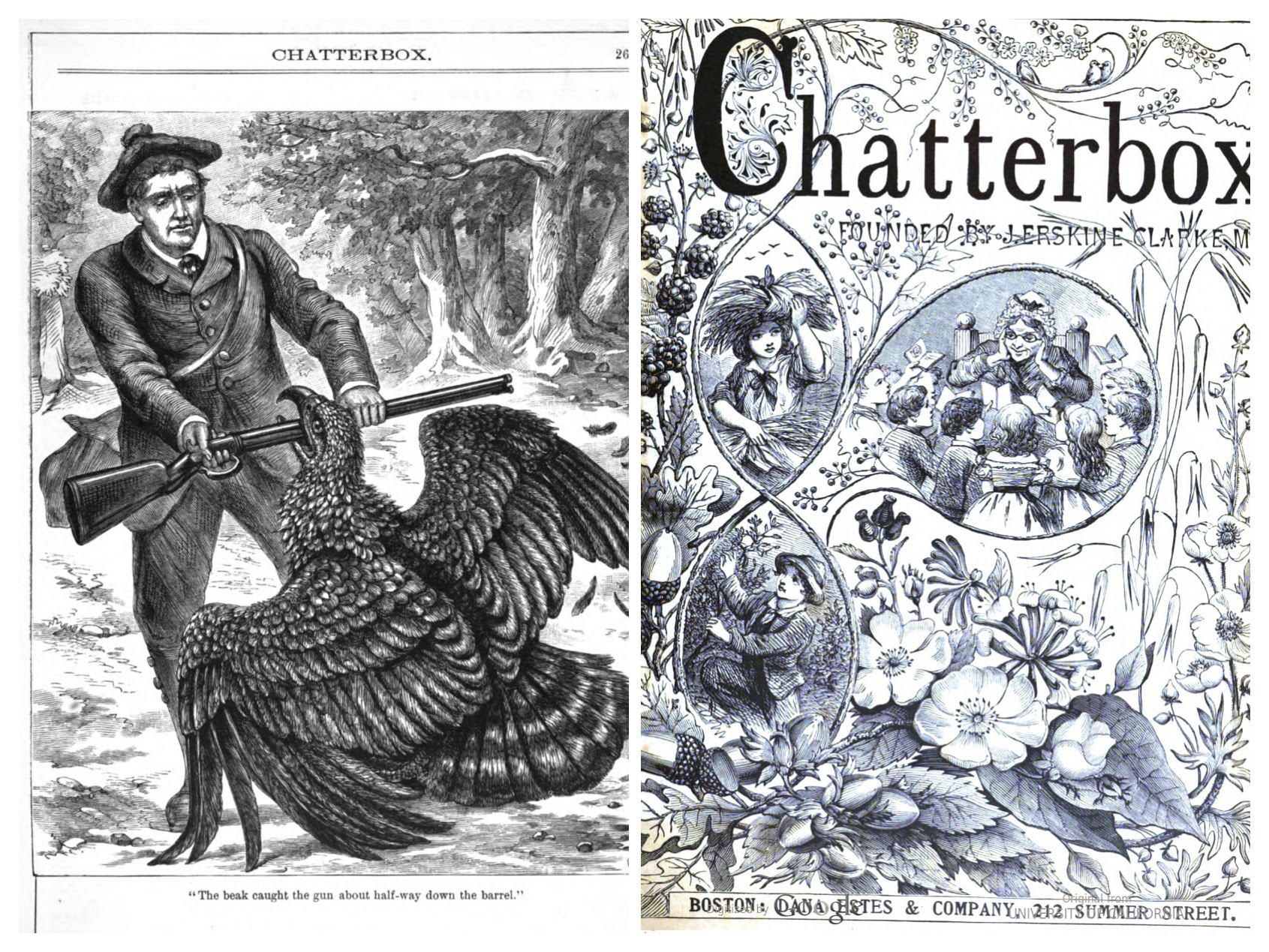

A relative gave us a framed copy of a rather curious engraving, it required further research to reveal the story behind the picture!

The image of a Scotsman wrestling with an eagle whose beak is clamped around his gun barrel suggests the hunter may have become the prey, or perhaps the eagle is taking revenge, which is true? And is this fact or fiction?

I started with the publication, indicated only by the single word at the top of the page “Chatterbox”. I had no idea what this referred to. A quick internet search revealed that Chatterbox was a weekly British paper of stories for children published in the 19th and 20th Centuries. It was founded in 1866 and ceased publication in 1955. It was sold both here in Britain and in the United States. It is typically Victorian and would definitely not be deemed suitable for children today!! There are in excess of 400 papers which I had to search through to find this one tiny article.

Although not especially child friendly, I found the contents of the Chatterbox papers fascinating. They offer an eclectic collection of stories from around the world about every subject you can imagine, delivered in colonial fashion via traditional plummy tongue. Clearly designed to be educational, there are stories of cats and frogs, of insects and butterflies, of native peoples and cultural customs, of medieval knights and Asian warriors, of survival techniques and men at war, of fashion and society people, of exotic countries and journeys through jungle and river…….and men hunting on great rural estates.

Within each annual publication is a section entitled “A Hundred Years Ago” which offers a story supposedly true in origin from that particular year one hundred years prior. The story about the man wrestling with an eagle was published in 1904. This is it, word for word:

TRUE TALES OF EVENTS OF THE YEAR 1804

VIII. – THE GOLDEN EAGLE OF WETHERBY

“Late in the year 1804 one of the Countess of Aberdeen’s game-keepers, Cummins by name, was walking in Stockfield Park, near Wetherby, in the pursuit of his ordinary duties, when he saw against the dull autumn sky what appeared to him to be an immense hawk, flying rapidly towards him, but some distance above his head. The bird was far larger than any hawk Cummins had ever seen, larger indeed than any English bird he had known; and accordingly, partly from curiosity and partly from fear, he let fly at it with his gun. A few feathers fell, but apparently the creature was unharmed. The game-keeper rapidly loaded and fired again, and even a third time. The last shot seemed to disable the bird’s wing, for it fluttered clumsily in the air for a moment and then fell heavily almost at the marksman’s feet.

But it was by no means dead yet. When Cummins tried to seize it, it drew its head back and with a sudden thrust tore a deep cut down his forearm, rendering the clothes as if they had been paper. In vain the game-keeper tried to get behind the infuriated bird and catch it by the wings. In spite of its wounds – for each shot had hit, and it had been struck in the wing, in the neck (very slightly) and in the body – it was surprisingly active on its feet, and its terrible beak and talons kept the enemy at safe distance. Cummins had almost given the attempt at capture up in despair, when a bright idea struck him. Picking up his gun, which he had thrown down so as to have both hands free, he made as if to strike the bird with it, rather slowly. As quick as thought the snapping beak drew back, lunged forward, and caught the gun about half way down the barrel, closing firmly round it, with the sharp point of the upper jaw fixed in the wood. Still gripping the gun hard, the bird allowed itself to be half-led, half-dragged by the game-keeper to his cottage, where, after a vain attempt, lasting many days, to tame it and heal its wounds, it was shot and stuffed.

After its death the enormous bird was examined, and proved to be not a huge hawk, as in the dusk Cummins had at first thought it to be, but the King of Birds himself, a Golden Eagle – and a large one at that, for it measured nine feet four inches across its out-stretched wings. No wonder it was hard to kill!

The Golden Eagle is now extinct in England and probably was practically so in 1804. It is still, though very rarely, seen in remote parts of Scotland and Ireland. It is not naturally fierce, for many instances are recorded of one having been tamed. But it is a most determined and courageous fighter when roused, a skillful and daring hunter, and by reason of its great size and strength a very dangerous opponent even for a man. One of the most remarkable things about it is that of all the small animals it preys upon – rabbits, hares, young lambs, and the like – it prefers the cat as its quarry.”

For someone who researches history for a living, stories like this are gold dust. Let’s not sugar coat it, this tale is typically Victorian and demonstrates a typically archaic and disrespectful attitude towards to animals. Why anyone would want to recount that disturbing story to a child is beyond me! It is however very normal for its day. Leaving morals and motivations aside for one moment, the interesting aspects hide in the detail. Recounted in 1904, the author tells us firsthand that Golden Eagles were extinct in England and had been so for a considerable time, as he indicated the situation had not changed in one hundred years. The extermination of the Golden Eagle in England is generally put at 1850 but stories like this suggest it was probably much earlier.

Even more interesting is that “Stockfield Park” must be a typing error, no such park exists near Wetherby but “Stockeld Park” does and is a large country house estate which was owned by William Constable at the time of this story. Wetherby is of course in North Yorkshire, not Scotland, so the unfortunate eagle was in England, an English eagle. But was it? It could have been migrating through, it could have been a lost juvenile, it could have simply roamed over temporarily from Scotland. It would be wrong to draw any solid conclusions without more facts. What I do know is that a nod is made to falconry even though the word itself is not mentioned (“for many instances are recorded of one having been tamed”). I am perturbed by the inference that eagles are dangerous to men and can only assume that their rarity in the C19th, a direct consequence of purposeful extermination, rendered the last few remaining eagles nervous and fearful of man, and perhaps defensive of territory which was interpreted as aggression with an intent to harm. Can you blame them? And finally, who knew that the golden eagle’s preferred quarry was in fact the domestic cat?! Perhaps rapid and aggressive land use change had robbed the eagle of his natural prey and he was merely trying to adapt.

All that from a simple black and white image. See, every picture does tell a story. Well, this is my interpretation anyway!

Emma. -

Chapter Six - The Life of an Extraordinary Kestrel - The End

22nd March 2021

The final chapter of my personal memoire. If you want to read from the beginning you will have to scroll down all the way to chapter one.

Chapter Six – Sunset

It has been many months since I completed the previous chapter and started this one. For good reason. Two devastating things happened in between which not only delayed my continuation of this book but changed its direction too. On the 11th March 2020, exactly a year ago to the day, a virus pandemic was officially announced by the World Health Organisation. There had been an outbreak of a new deadly virus in China and it was rapidly spreading around the globe. Two weeks later a national lockdown was announced in the UK. I had just returned from a trip to Sweden and only just made it back before air travel ceased and the country ground to a terrifying halt. All our commercial bookings for the year ahead were cancelled and suddenly we faced a total and prolonged loss of income. Within the space of a single week, we went from facing our busiest and most lucrative year ever, to potential bankruptcy. Finishing this book no longer mattered as the fear for survival took over. We spent weeks trying to sort out our finances, negotiate contract settlements and claw together some financial protection. Like millions, we were scared and anxious and uncertain of our future. And then, in the middle of all the chaos, something even worse happened, Pageant died just 2 months short of her 21st birthday.

For the last two years I knew Pageant was living on borrowed time, her strength in flight was waning, and her eyes had become milky with creeping cataracts. I had her blood tested to check her organs were still functioning adequately, she had arthritis in one of her wing joints which needed anti-inflammatory treatment, and she had developed gout in one foot which required daily drugs. The signs were all there, her time was running out, all I could do was to keep her comfortable and pain free. I still flew her regularly but had to be more careful as she became less able, her flights were shorter, lower, safer. That February we had visited a museum in Stoke-on-Trent during half term to give indoor presentations about the use of birds during WWII, Pageant had come with us of course as this was just kind her kind of job. In one of my presentations, I recounted the story of a soldier who rescued an injured wild kestrel he named Cressida, he became so attached to her that when he was stationed abroad, he took her with him, but he was captured and spent the remainder of the war being moved between PoW camps. Miraculously he managed to retain possession of his kestrel throughout the war, surviving starvation, injury and separation until liberation came. Cressida charmed everyone she encountered, and because of the dedication of her handler, made it safely back to Britain. It is such a staggering, heart-warming story that I cannot recommend it highly enough (The Lure of the Falcon by Gerald Summers). Unbeknown to me, the visitor manager of the museum had been listening to my account, she approached me quietly at the end to say how much she had enjoyed the tale, and that she had noticed I got emotional despite me trying to conceal it with deep breaths and careful pauses. She was right, I had fought back the tears and choked on emotion more than once during my public delivery because the story was deeply personal, it reminded me so much of Pageant, she was my Cressida, and I knew I didn’t have much time left with her. It was Gerald’s story that inspired me to write my own, and I wanted to do it while Pageant was still alive, so the memories were fresh and not filled with sadness. I didn’t quite make it.

The last job we ever took Pageant to, was a private event at Witley Court in Worcestershire on the 3rd March. She enjoyed her day trip and the stimulation of getting out and about at the end of a long winter. That was the last time she travelled on her special perch in the van, the gout in her foot made her a bit unbalanced as she tried to compensate for the movements of the vehicle, so she spent most of the journey sat on my shoulder leaning against the side of my head. As we left Worcestershire, I made the decision to retire Pageant for whatever time she had left. No more travelling, no more flying, even though she loved both, because I needed to keep her safe. We had never been able to house Pageant free in an aviary, we tried on numerous occasions over the years only to find her hanging off the netting or hanging upside down from the roof, she was a liability and likely to hurt herself. Not all birds adapt well to aviaries and Pageant quite literally smashed herself to pieces. She was much more content tethered in a weathering (sat on a perch in a shed), and because we flew her so much, she didn’t need the freedom of an aviary. However, with gout causing her foot to swell, I no longer wanted jesses on her afflicted leg, and a bird cannot be tethered by just one leg, so it was time to re-visit the aviary option. We ended up converting a small hawk loft into a retirement aviary, installing ramps so she could get from the floor up to the high perches with ease, and making a shelf for her food and her water dish. She would sunbathe on the carpeted ramp and shuffle along her beam perch following the warm rays as the sun tracked across the sky. At her superior vintage, she behaved well inside the aviary and did not attempt to hang off the netting or throw herself about, although I still put her to bed every night inside the heated bird room, so her routine was the same as it had always been. She sat and watched the wild birds, and the cats, and my husband and I milling about the garden, and she seemed content. It was early spring and the days were getting longer and warmer offering Pageant plenty of opportunity to sunbathe, which after eating was her favourite pastime. I took a photograph of her soaking up the sun on her ramp, little did I know it was the last photo I would ever take.

Pageant had been in retirement for only two weeks when I noticed one morning that she had vomited up a lot of undigested food. She was a little subdued but drank and sunbathed as normal, I resolved that if she still looked unwell the following morning, I would have to try and take her to the vets. The nation was two weeks into a strict lockdown after the coronavirus outbreak, society had shutdown and accessing a vet was suddenly extremely difficult. My heart therefore sank like a stone the following morning when I discovered Pageant had rapidly deteriorated overnight. The end was coming, and she needed my help more than ever. I knew instantly what I had to do, she had to be put to sleep. I wish I could say it was a smooth process but with coronavirus restrictions it was not. Clients were not permitted to enter the veterinary surgery so had to pass their animals over to a member of staff in the car park. I was told when the vet came out to collect Pageant, that they might make an exception for euthanasia, he would speak to the practice manager, but they got on with the procedure without coming back to me and so I didn’t get to say goodbye. I was heartbroken. For me, that was the worst possible ending, it meant I didn’t keep my promise to never leave her. I could have complained but I was numb and devastated, the pandemic robbed so many people of so many things, I wasn’t a special case and I couldn’t change what was done. We drove home in silence, I was unable to speak and fearful of letting my guard down before we reached the privacy of home. We buried Pageant that afternoon alongside Lute, Altair and Beauchamp, three of our greatest birds who all died before their time from incurable conditions. It was a beautiful sunny day, a peaceful day to put her to rest, and we marked her grave with a tall, enamelled metal poppy which we can see from the house. I didn’t want to place her somewhere quiet and unseen, Pageant would have hated that, she was always at the centre of life. Now I imagine her sat on her great travel perch in the sky watching everything going on in the garden like she always did, and maybe, just maybe, hovering above me as I go about my duties. The thought of that makes me smile.

Nothing will fill the hole she left, and no bird could possibly replace her, but it hasn’t stopped me trying. For years I have attempted to find an understudy for my leading lady and each time I have failed. Many kestrels have come, and gone, in the tireless search for a Pageant II. There was “Autumn” in 2008; a parent reared female kestrel who was a great flier but far too nervous for our public work, she was given to an old friend who had always wanted a kestrel who flew to a lure, which Autumn did. In 2012 I acquired “Biscuit”, a young female who flew like a demon and hovered like a proper kestrel should, I loved her dearly and thought she was the one, but in her second year she went high on the soar one hot sunny day and tragically got chased off and killed by a wild buzzard. In 2015 the opportunity to buy a pair of young kestrels arose so I thought I might train them to fly together, it worked brilliantly on home turf but not at events where the male was perfectly behaved but the female always flew off. I contemplated keeping just the male kestrel and rehoming the female, but they were inseparable meaning I would have to find them a home where they could stay together. Fortunately, a friend who runs a falconry school was willing to take them and they still happily reside there together today. By this stage I realised that my efforts were always going to be fruitless, Pageant was unique, she could not be cloned, and I needed to stop trying for the impossible. I promptly abandoned my search. I have neglected to mention that I have always had a second kestrel in addition to Pageant, well maybe not always, a male five years her junior called Bodkin. He is a delightful little chap, handsome, extremely sociable but never as reliable as the formidable Pageant. He always hated her with a vengeance, while she was merely belligerent towards him, they reminded me of the two rival babies in The Simpsons animation and consequently had to be kept well apart. Bodkin was always there in the background never quite hitting the big time, I mean, how could he possibly compare to Pageant? And now she is gone, it is too late for him to step into the limelight. Male kestrels tend not to live as long as females, so he too is now entering his twilight and has already been retired. Poor Bodkin, always the page boy, never the groom.

Four years had passed when by chance I noticed an advert while searching the internet; an 8-month-old hand reared female kestrel was for sale, looking for a new home because she did not get on with her handler. I was intrigued, I had never known anyone not to “get on” with a kestrel! I drove three hours to go and see her, and the second I clapped eyes on her she was definitely coming home with me. Not because she was perfect but because she was being kept in such a poor state. That is how I ended up with “Celeste” who, as it turns out, really hates men! Mike has to hide when I fly her or she hunts him down and pins herself to his head! Fortunately, her handler is now a woman and we get on extremely well. I acquired Celeste one year before Pageant passed away and hoped I might have accidentally found her replacement, but with her social and behavioural issues, she still isn’t the one to fill Pageant’s mighty shoes. So along came “Griffin”, the last of my kestrel lineage and my 2020 lockdown project. She was unplanned but arrived at the perfect time. I hand reared this kestrel myself, spent the summer slowly training her to fly, took her to just a few public events during the autumn, and continue to bring her on slowly and carefully even today.

On reflection, and there has been a great deal of it during the last twelve months, the only good consequence to come from the pandemic is time. I have all the time in the world to nurture Griffin, just like I did Pageant in those early years, and if Griffin lives for anywhere near as long as Pageant did, she has all the time in the world too. Living without Pageant has been difficult, but the fact that she reached such an extraordinary age in my care, despite her catalogue of adventures, is all the comfort I need.

Pageant – Falco tinnunculous – May 1999- 29th March 2020

The End.

I hope readers enjoyed sharing my experiences of a very special little bird. If I ever possess a bird even half as magical as Pageant ever again, I will consider myself blessed.

Thank you for reading. Emma x -

Chapter Five - The Life of an Extraordinary Kestrel

15th March 2021

The penultimate installment of my personal memoire. Scroll down for previous chapters.

Chapter Five – Little Ray of Sunshine

Pageant has always brought a lot of joy to my life because she is so full of life herself, she has consistently thrown her little self into everything and done it with gusto. For all those scrapes I got her out of, she helped me out of far more of my own. I hate to anthropomorphise animals, but she genuinely has a lot of character, too much character! It doesn’t feel comfortable saying that because birds of prey are generally quite linear, black and white creatures, but Pageant had a little extra spice about her from the beginning. I wouldn’t be the first falconer to admit that. Once in a while, a bird comes along which just charms the pants off you, I consider myself lucky to have had at least one. Pageant was cheeky and charismatic from the get-go, and big, larger than any other captive bred kestrel I have ever seen. I always put that down to good genetics. Every captive bred kestrel I have purchased since, and there have been a few in the tireless search for a Pageant mark II, has been small and delicate whether male or female. I am told that decades of captive breeding eventually breeds out the need for size, a form of natural selection, which would probably explain it. I realise now that Pageant’s size is partly responsible for her abundant confidence, from the moment I first flew her, she was bold and capable of taking on the world with both wings tied behind her back. Nothing really scared her, not even when we introduced a Golden Eagle to the flying team. Some of our hawks, much larger than Pageant, were terrified when they first clapped eyes on the giant predator, not Pageant, she didn’t care one jot. But I am convinced that Pageant has no concept of what she is, she was hand reared by a human and not a kestrel after all, so perhaps in her head she imagines herself as large as her human parent. That would explain her bravery. So yes, she is a bird of immense character.

Mike and I calculated that Pageant has participated in more of our events than any other bird on the team, she has always flown year-round unlike some of our big gun falcons, she has been flown by more volunteers/students/trainees than any other bird, and travelled more widely than any other bird, including on tens of ferries to the Isle of Wight and the Channel Islands. We routinely mend more of her broken feathers than any other bird in our care because she is so mobile and active. My goodness has that bird flown a lot during her life! And that is when we have had the most fun together. But she has a handicap, a big handicap for a kestrel – she will not hover! Not ever. We know she is perfectly capable of performing that most natural action for her species, and very occasionally we get a fleeting glance of a hover if she gets caught by the wind, but she will not sustain it, nor can she ever be persuaded to do it on demand, so I gave up trying years ago. Most falconers spend a lot of time training their kestrels to hover, it can be achieved quite simply by employing a combination of food presentation and strategic positioning according to the wind direction. Many kestrels hover so naturally they don’t even have to be encouraged. Not Pageant, no way. She learned early on that hovering was not necessary, it was an action superfluous to need when one was not a wild kestrel, and frankly it was too much effort. She was going to get fed anyway so why did she need to hover? If I ever tried to get her to hover above me, she would simply land on my head and make me look incompetent, as if to say “told you I wasn’t doing it”. Imagine my delight therefore, when someone emailed me a photograph of me flying Pageant at an event and there she was, hovering above my head! I was oblivious, had no idea the little munchkin was lurking above, but now had the evidence captured for posterity. I decided years ago that Pageant has a personal motto; “I could, but I choose not to”. Emancipation apparently applies to kestrels too!

When I reflect on Pageant’s flying ability, for the most part she was always a boomerang bird; I could cast her off into flight, pop a small piece of food on my glove and know, without even looking, that she was already on her way back to me. A reliable falconry bird which responds instantly to recall is pure gold and she was like that from the start. But she never missed a trick and took full advantage of my human errors. Like the time I cast her off to a tree while exercising her in the meadows at home, I accidentally dropped all her food on the floor so bent over to pick it up not realising even more food fell out of my pocket as I did so. By the time I stood upright, Pageant had spotted the meat, stooped out of the tree at speed, snatched it off the ground and flown back up to the tree with it. The whole scene happened faster than the blink of an eye, certainly faster than I was able to comprehend and react to. What was the problem you might ask? When a trained bird of prey grasps its meal in its feet and then gets away from you into flight, you normally spend the remainder of that day (and sometimes the following one) chasing it across the countryside. A falconry bird will only come to its human handler for a food reward, therefore, if it possesses its own food the human is rendered redundant. That was me at that very moment, obsolete and without purpose, staring at a thoroughly victorious kestrel sat in a tree with a large chunk of meat, her personal motto ringing in my ears. She hopped from branch to branch and I feared soon enough she would take flight and disappear over the horizon with her prize, but to my relief she did not. Once she had found a suitably comfortable branch she started to eat. I stood completely still, held my breath, and did not move a muscle for the whole time it took her to feed, scared that any distraction would spook her into flight. Once the little monkey had finished her meal and wiped her beak clean on the branch, to my surprise she instantly looked towards me for more. Pageant has always been a greedy gut, even after a good meal there’s room for a little more, so when I placed a second helping of food on my glove, even though she had a full crop of meat, down she came without hesitation. That could have been a nightmare day, so thank goodness Pageant is a proud glutton!

About ten years ago there was an incident where Pageant entered a public tearoom without being invited, much to the amusement of the queuing customers. She wasn’t looking for food, she was just lost. This occurred at Dunster Castle in Somerset where we performed several times each year, so Pageant became very familiar with the grounds. The castle is positioned high on a densely wooded hill, and although the flying location was sheltered, above the treeline was often quite breezy and Pageant would sometimes catch the breeze and go for a little wander. We never worried, we just had to give it a couple of minutes and she would always find her way back, popping up somewhere on the castle wall or the tower of Tennant’s Hall. Apart from the one occasion when she didn’t reappear. Knowing how long to leave it before going to investigate was always tricky, many times we gave up on her too soon and she would come sailing back over just as one of us was running out of the event arena to go find her. This time around she had been absent for about two minutes which feels like an hour when you are in the middle of a public demonstration, I was explaining to our audience that we were going to close the show and go searching for Pageant, Mike was ahead of me climbing over the arena barrier in the direction we last saw her, when the people at the far end of the arena started to wave and point, not up in the sky or towards a tree as you would expect, but through an arched doorway in the castle wall….which led to the tearoom. Mike ran to follow the hand signals, passed through the arch and was stopped by someone who said, “you looking for a bird?”. He was directed through the tearoom door and there sat Pageant on the serving counter among the cakes and scones in their domed containers. “She was very well behaved, she just sat there” said one of the ladies in the queue. Everyone thought she was charming, even though she broke every food hygiene rule in the book, no-one knew what to do, so did nothing, and were mighty relieved when she was safely collected. It turns out she had entered through an open kitchen window and hopped her way along the work surfaces to the main counter, with no obvious way out, she just sat and waited to be rescued. She knew we would come eventually; we always did.

Pageant has spent all her life travelling. You will recall she has her own unique way of getting about and it was always a riot, I say “was” because we travel her a little less rigorously now she is very elderly. For every journey whether a short trip or long haul, there she would sit happy as Larry on her little seat perch watching the whole world go by outside the window screen. We have had 2 black Labradors over the years, and both had to endure travelling with a kestrel perched above them, neither interested in the other as they were raised together, but the dogs at a significant disadvantage. They both lay in the danger zone beneath Pageant’s bottom, and both would exit the van after a long journey striped like a badger! We never did find a way around this so just carried many packs of wet wipes to counter the hot, watery jets fired indiscriminately from above. Pageant loved water, she drank lots, and lots, and lots which made travelling with her very messy. The human passenger was at risk if she decided to turn her tail before dumping her waste, which she did at least once per journey and normally within the first hour when she had the greatest load to dispose of. Many of my hooded tops ended up with a hood full of kestrel faeces, goodness knows how many times I must have walked into a petrol station without knowing I had a long streak of poo all down my back. We got so desensitised to it my husband would never bother to tell me. The shame! So I started to keep a spare jumper in the van at all times. Sometimes a new contract worker or trainee would ride in the passenger seat, but we would forget to warn them, so they would be christened by Pageant like a surprise induction ritual. A horrific one! If there was sunshine streaking through the wind screen, Pageant wanted to be in it, so you were never allowed to put the sun visor down, you just had to suffer the glare and go blind. If there was a traffic jam or slow-moving traffic, Pageant would get agitated, she much preferred to see cars whizzing by at speed. She also preferred motorways to local roads, they meant more speed and fewer bends, but motorways increased the chance of seeing buzzards and kites, which, by the way, she HATES. Travelling also meant spotting a lot of hovering kestrels whom Pageant considered to be intruders, flicking her tail in anger at the audacity of their presence. She owned the roads, not them! She would sit up there on her travelling perch, day and night, rain and shine, through thunderstorm and snow blizzard, crossing bridges and sailing on ferries, taking it all in. I came to recognise that she had two favourite views; across the estuary from the M25 Dartford bridge, and from the M5 across an enormous valley somewhere near Weston-super-Mare. She would raise all her head feathers, point her head forwards and stare as if in complete awe at the expanse of her view. The novelty of her travelling position even once helped us to avoid a speeding ticket because the policeman was not expecting to see a kestrel when he bent down to talk through the window. Subsequent kestrels would never take to travelling this way but in truth, I am whole heartedly glad that it is a trait unique to Pageant.

When you make a living from demonstrating birds in flight to the public, it is not uncommon to be upstaged by your feathered co-star. Pageant has excelled at this throughout her life and is most entertaining when she can publicly embarrass me, something which happens all too frequently. She has landed on my head during numerous shows only to cause my historical headdress to fall off – and trust me, that’s a big fat nightmare in the middle of a public performance. I have lost Medieval headdresses, Norman veils and Roman hair pieces to heavy kestrel feet. She has been known to dive into my falconry bag and hang off the side in an attempt to help herself to food and has often been thought lost only to find her quietly hanging about above my head perfectly hidden in my blind spot. Many times have I heard sniggering from the audience as my kestrel reduces me to a blundering fool. Quite recently, she decided to turn her part in a medieval event into a comedy show when she caught a huge beetle; she was in mid-flight when she suddenly stooped towards the ground and pounced on something, she then proceeded to jump up and down and run around in circles, whereby, on closer inspection, I could see she had caught a large black beetle which kept escaping her until she ran after it and caught it again. I bent down to try and pick her up (and put an end to the nonsense) but she ran away from me at speed, with her beetle! She wasn’t going to be parted from it or have it stolen from her. The next five minutes were like a scene from a Benny Hill sketch, with a medieval lady comically chasing a sprinting kestrel round and round the grass. It must have been one of those beetles which excretes a bitter defensive substance because after squashing it with her beak a few times, she spat it out and shook her head vigorously as if it tasted very bad. Birds of prey in fact cannot taste, but they can detect extreme bitterness – thank heavens because the show could not have gone on without getting Pageant back, with or without the beetle.

In her latter years, I noticed that Pageant started to feel the effects of cold weather more and more. I would worry about her overnight even though she has always been put in a mews box to sleep. Her box could be moved around so it often got brought into the house where she could benefit from the central heating, until we installed a wall heater in the garage. When we moved house some years later, we converted an old detached garage into a custom built bird room which was insulated and heated so I never had to worry about her again. It remained a problem however, when we travelled away to events which meant staying away from home overnight. I secretly smuggled Pageant’s box under cover of darkness into many a B&B and hotel room, she has slept in her box inside airing cupboards, ensuite bathrooms, boot rooms and under stairs cupboards, anywhere quiet and warm. No other bird has ever been pampered in this way. We have even started taking a gas heater with us to events so we can keep her warm inside our many marquees. And that is why, for the last three winters, Pageant has spent various odd days sitting on a perch in my office when outside has been a snowy apocalypse. I have a large table which, once cleared, houses a free-standing perch and a water bath on a carpet mat. She sits looking through the front window, watching the pigeons and the moorhen on the front lawn, ignoring my two cats and them ignoring her. A most unusual scene of harmony but not uncommon in my household. She is quite good company as an indoor companion and has watched me sew, type, draw, hoover and paint with interest, the only downside being that one must be on constant poo watch because the more she drinks, the further she can fire it!

My husband recently reminded me of an incident I had completely forgotten, probably because I wasn’t there to witness it myself, but Mike was, and so was Pageant. An unforeseen moment when Pageant brought sunshine to a group of special people on a very dark day. It was the summer of 2002, Mike was working part time as an avian pest controller on various landfill sites across Norfolk and Cambridgeshire, and it was the time of the ghastly Soham murders involving the disappearance of two little girls. Forensic police had been searching one of the landfill sites at which Mike worked, they had been there for days sifting through the rubbish and waste, it was a dirty and depressing job, and deeply traumatic for those involved as they desperately looked for human remains. Morale was so low that the chief of the investigation, who had heard there was a falconer on site, came to see Mike to ask if he might fly some birds for the forensic team, to raise their spirits and give them a distraction before they resumed their duties. Mike always took two falcons and 2 hawks to that particular job, but by chance he also had Pageant with him that day as he was planning to fly her in the adjacent meadow during his lunch break. What better bird to fly as light entertainment for a group of people who desperately needed their minds taking to a happier place? That’s Pageant all over, a little ray of sunshine who has touched tens of thousands of people during her lifetime. One special little bird indeed.

Final chapter coming soon. Copyright Emma Raphael.

-

Chapter Four - The Life of an Extraordinary Kestrel

7th March 2021

The next installment from my personal memoire about the oldest and best kestrel in the world! Only 2 more chapters to go…

Chapter Four – A Series of Unfortunate Incidents

I have already dealt with some of Pageant’s troublesome scrapes in an earlier chapter, but they were of a minor grade with no lasting effects. However, a bird of Pageant’s age cannot have escaped a few more serious incidents bearing in mind the distances she has travelled and the variety of bizarre locations in which she has flown. Those stories, thankfully few, arise from a series of unpredictable and unfortunate incidents, which without careful management, could have resulted in a fatality. However you cut it, flying birds is risky, because the big bad world is full of hazards just waiting to get you. Imagine the rollercoaster that each day brings for a wild bird, never knowing from one day to the next if it’s going to see another sunrise. My birds are wrapped in cotton wool in comparison to their wild cousins, protected and pampered all their lives, but even they are not immune from danger.

In her youth, Pageant would travel with us to Fort Nelson, one of the Royal Armouries museums in Hampshire. We performed both Victorian and WWII period falconry on the parade ground and would visit two or three times a year. Pageant was a great bird for that environment; a hard surface military fortification with high grass embankments, lots of roof tops, lamp posts and cannons – loads of places for a kestrel to perch up on during flight. She was a cracking little flier at the fort and so always came along. Gaining vehicle access to the fort was a lengthy process; it required us to park up on a sloping track in front of the tall main entrance gates, then run halfway round the outside of the fort to the visitor entrance to announce our arrival before being granted entry. Two members of staff had to be called by radio to attend the gates and open them together, after clearing visitors away from the area, and this all took time to put into effect, so sometimes we would be waiting for up to 20 minutes outside. During one visit it was incredibly windy, the wind was whistling around the fortification and gently rocking our van. The fort sits high on a hillside looking strategically over Portsmouth harbour so on a windy day it is very exposed. Pageant was tethered on her travel perch to the side of the passenger seat headrest, between the seats, and was merrily preening her feathers while we awaited access. My husband took our dog for a brief walk and opened the side loading door on his return to let her jump back inside the van, by coincidence at the same time I opened my passenger door and climbed out, the force of the wind against the door immediately slammed it shut again just missing me. The power of the slam jolted the side loading door out of its catch, and because we were parked on a slope, the sliding side door gained momentum and rapidly shut. At the very last second, and goodness knows why, Pageant decided to bate towards the door, that’s the action of trying to fly forwards. To my horror, I could see that she had been tethered to her perch with too much length on her leash, she should not have been able to reach the side door at all – but on this occasion she did. Her head filled the gap between the door and the frame just as it slammed shut.

I can honestly say I have never felt as instantaneously or as deeply nauseous as I did at that moment, as though my stomach plunged to the floor and my heart stopped. She’s dead. That was the only thought in my head as I fought to open the door. I feared looking inside afraid that our negligence had resulted in tragedy, I expected my precious little companion to be crushed and lifeless and it would have been my fault for not concentrating, not doing my job properly. I couldn’t live with that. The sorrow was choking, sickening. When we carefully peeled the side door back Pageant was not dead, she was however clearly injured. The relief was fleeting. My little girl had scrambled back up on to her perch somehow but was hunched over with her head dropped and one eye completely shut. If this happened to me today, not that it would with lessons having been learned the hard way, I would dash straight off to my specialist exotic vet, but we had no such vet two decades ago. We were a long way from home and did not want to put Pageant through a lengthy journey in her delicate state, it was late in the afternoon and we wouldn’t get home until after dark now, so we had to make some decisions and fast.

First things first, examination and assessment. We have always carried a comprehensive bird first aid kit with us so were not completely helpless. The first rule with any sick or injured bird is to keep it quiet and warm so we vacated a travelling box, lined it with carpet and placed Pageant inside. She was on her feet, not seeking to lay down, so we were comforted a little by that. It was June so the van was adequately warm, we finally gained entrance to the fort so drove carefully to a quiet spot in the private area and parked up. This gave us the opportunity to examine Pageant more carefully, apart from a patch of feathers missing on one side of her head there was nothing visible. She was clearly badly bruised and a little shocked, so we treated her for the shock with a restorative liquid fed by tube directly into her crop, we administered some anti-inflammatory pain killers, and then left her alone in her box to rest. Had we been at home we would have done nothing more and a vet would only have pulled her around and x-rayed her which would not have helped. Today a bird can be quickly and safely anaesthetised for inspection, but 20 years ago the process was not so refined and the risk of anaesthetic death for birds, particularly small ones, was extremely high. We checked on Pageant every hour and were satisfied that she was at least comfortable. We were staying on site overnight in the education room so took her box indoors with us and kept her warm. The next morning, she was still wobbly but far more active, she wanted her food as normal which was the best sign we could have hoped for because when a bird of prey refuses to eat it is an indication that something is terribly wrong. Her eye was still half closed but she was vocal, fully responsive, and able to eat. We transferred her back into the van and put her a little water dish in her box, she sat there quite comfortably and quietly on her perch with the door open. There was a narrow ray of sunshine streaming through the windscreen that just happened to fall on Pageant, so she sat there soaking up the warmth with her feathers roused. We got on with our day of work and looking after the other birds we had with us, Pageant remaining in the peace of the van the whole time, and our host venue oblivious to our private drama. Every time we checked on her, she had shuffled around to remain in the sunshine as it moved through the day, and by the afternoon, after a second meal, she began to contentedly preen her feathers. At that moment we knew she was going to be ok.

Pageant was now strong enough to safely travel so we were greatly relieved to arrive home later that evening and put her to bed inside the house. The following day her eye was examined by our vet and thankfully there was no damage, just some tissue swelling which gradually reduced with a continuation of the anti-inflammatories. Pageant became a house kestrel for two weeks during her recovery, and we left her with a friend when we had to travel away for work, so she had a full month of rest and recuperation. I am pleased to report there was no lasting damage other than to my own self-confidence for mis-managing my favourite bird. All these years on I have still not forgiven myself. Pageant went on to fly for many more years and continued to travel about with us on her seat perch – but on a strictly shorter leash. Over the years we progressed to using larger commercial vehicles which afforded her more room and automatically kept her further away from the dangerous side door. Remember, she would not accept travelling any other way!

Pageant had a second close shave some years later when she got hung up in a tree. This is an unlucky accident for a falconry bird to have and generally results from flying a bird in the wrong leg equipment. The leather straps which hang down from a hawk’s leg are called jesses, they allow the falconer to hold and secure their hawk, but they are not necessarily safe to free fly a bird while still wearing them. The jesses can get caught up in branches should a hawk land in a tree, so traditionally we use two types of jesses: one for tethering a bird to its perch (mews jesses) and one for flying a bird free (field jesses). The mews jesses contain a slit in the end of the leather straps through which a metal swivel can be attached to conjoin the jesses to a leash, for the purposes of tethering. Once the swivel and leash are removed a hawk can then be flown wearing the remaining jesses however, the slit in the mews jesses can open and snag on things like branches, it is extremely dangerous and increases the chance of entanglement. If an entangled hawk is not found or recovered quickly it can of course be fatal. Good falconry practise requires mews jesses to be changed for field jesses before flying, which means replacing the straps with slits for slightly shorter straps without slits. It is a fiddly job but takes very little time to do and vastly reduces the risk of entanglement. I have always slipped the mews jesses out and replaced them with field jesses before flying and it has served me well during my time as a falconer. I have never had a problem with entanglement, except for that one time with Pageant.

We were exhibiting at a country house in Essex, I was in the middle of flying Pageant who was winging about through the arena and perching up in trees. Mike had made some new flying jesses which had their first use that day, a lovely soft, thin burgundy leather cut into little straps with NO SLITS! Pageant’s old jesses had become stiff and dry despite oiling them frequently, so it was time to change them. Mid demonstration she pitched up in a horse chestnut tree, sat there a little while and then tried to return to my glove, but she couldn’t, she flapped and fell forwards until she hung upside down. She had grabbed hold of a narrow branch with one foot and her toes had locked around it, she was unable to let go immediately and so swung backwards and righted herself from behind the branch. We call this being “sticky-footed” and it refers to the ratchet mechanism in a raptor’s foot, the fact that toes can temporarily lock in place to hold prey, a great system but one that takes a little time to release. Phew I thought, she will relax her foot in a few seconds and then she will be able to fly back to me, but she didn’t, she flopped forwards once again, and this time could not scrabble back into an upright position so hung upside down like a bat. Pageant flapped and flapped and flapped to try and right herself, I abandoned the demonstration and ran beneath the tree to get a better look. She was about 15ft high and I could see that her leather jess was completely wrapped around a tiny narrow branch. Righting herself the first time by going up behind the branch had caused the jess to completely encircle it, and by continuing to flap forwards she was tightening its grip. A couple of minutes had passed by now but that was enough time for Pageant to begin to tire, she ceased struggling and just hung there. This was now a rescue mission.

Mike and I plus many members of our audience were hurriedly discussing what to do; someone ran off to try and find ladders, a young chap offered to climb the tree but the branches were too thin to support any weight, Mike thought about driving the van over so he could climb up on the roof to reach her but getting to the car park and back would take a lot of time. Then one gentleman suggested standing a nearby park bench on its end, using the slatted seat like a ladder, and climbing up to stand on top. Genius! It took six people to lug a very heavy and long wooden bench over to the tree, everyone supported it with their weight and an extremely tall man volunteered to climb up. Minutes later dear little Pageant was rescued. She allowed the rescuer to fold in her wings, scoop her up in his hands and hold her upright. He snapped the entangled twig with his fingers and passed her carefully down below. This man had no experience of handling a bird of prey, he just wanted to help, but it seems in the panic of the moment he instinctively knew exactly what to do. Pageant was unhurt, just exhausted from all the flapping. That pesky twig was still attached to her field jesses, wrapped tight like a ribbon, ironically because the leather was new and supple. Had I used her old flying jesses which were stiff like thick paper, well, the accident would not have happened. It would seem that by trying to do the right thing, I did the wrong thing. Or was it simply a case of bad luck? Either way, after this incident we started to use slightly thicker leather for all our flying jesses, or to remove jesses completely, and touch wood we have not had a repeat. Pageant continued to land in trees quite happily for the remainder of her life thankfully unaffected by the drama in the horse chestnut.

The only other occasion when Pageant had a close shave with the grim reaper was at Pickering Castle in North Yorkshire when she was 5 years old. It was early spring and the weather had turned suddenly cold. We were working solo at the castle, there to perform medieval falconry, and it was a challenging venue with no vehicle access and restricted airspace, but as always we did our best. On the first day of our weekend event, Pageant looked a little off colour, she was unusually quiet and still which was not normal. Her eyes were a little sullen and she sat with her feathers fluffed up as if unwell. When you know an animal, you know straight away when something is wrong. She had dropped a lot of bodyweight overnight despite seeming perfectly healthy the day before, the tolerances for little birds are small, so her loss of half an ounce clearly affected her starkly. This explained her lethargy and lack of energy, so we fed her a meal straight away dipping her meat in a special recovery liquid. We always carry a couple of frozen “emergency mice” with us for just such instances, although on this occasion they were Russian hamsters because our food supplier had run out of mice (we jokingly called them Russian cosmonauts – apologies to anyone with a pet hamster), so we heated up the interior of the van and left Pageant in the warm all day with a large Russian cosmonaut. She perked up nicely but when we weighed her at the end of the day, she still hadn’t gained any weight. A thick frost was forecast overnight and that left us even more worried about Pageant’s health. We were due to camp overnight in the castle education room which had heating and hot water, we were obviously going to have to take Pageant indoors with us overnight, but then we noticed that adjacent to the education room was a barn with double doors – built to accommodate a vehicle. Our door key, loaned to us by the castle custodian, also unlocked the barn so we had a quick look inside. We expected it to be full to the ceiling with shelving, stock goods and storage items making it impossible to squeeze a van in, and although there was some stuff inside, there wasn’t so much that it could not be moved aside to make space for a vehicle. So that is exactly what we did. With permission, we parked the van indoors overnight in a heated building which felt like a huge victory, all the birds were safe but particularly Pageant who, despite a second meal, had only managed to maintain her weight rather than gain more. Fortunately, her weight did increase the following day after another stay inside the van hugging yet another Russian cosmonaut, and by the time we went home on Sunday evening she was perky and absolutely fine. There is no doubt, the combination of a warm barn and some fluffy foreign rodents saved Pageant that weekend. Ypa! (that’s Russian for hurrah). We were jolly lucky to have the right facilities at just the right moment!

Leaving all the previously described dramas to one side, the absolute worst thing that ever happened to Pageant is something that I consciously and purposefully did to her. I find it hard to admit, I am ashamed to admit, that I gave her away. I took her from her comfortable home and a loving owner, and I sent her to live somewhere else with someone she didn’t know. I regretted it so much I made myself sick. I remember the anguish like it was yesterday. A week prior, one of our regular clients had made a passing remark after watching our display at an event, they commented off-hand that while the larger birds (the hawks and falcons) were impressive, it was more difficult for the audience to see a bird as small as a kestrel flying inside a large arena space. It was insinuated that if we wanted more work in the future, we should perhaps take this into consideration. If someone had the brass to say that to my face today, I would wipe the floor with them, the arrogance! But this was a long time ago, my husband and I were still finding our commercial feet and our confidence was low. We took the (unprofessional) remark to heart and returned home to consider restructuring our flying team. We had a friend who ran a small falconry centre, she was looking to buy a kestrel that year, so this seemed the obvious place to send Pageant to start a new life. I could not bring myself to put a price on Pageant’s head and sell her, so she was given as a donation, not that it lessened my guilt one iota. She jumped after me as I walked away and I couldn’t bear to look back. Leaving her and driving off was the worst feeling ever, it was a total betrayal. I cried the whole way home, I cried in the bath, I cried through the night. The next morning I woke in a flaming rage; how dare anyone tell me which birds I should and shouldn’t fly, no-one is that important, no-one! And how utterly stupid and naive I was to even contemplate putting a customer’s needs before those of my own bird. But as we quickly learned in those early years, it was easy to get taken advantage of and to be manipulated for no other reason than allowing someone else to feel powerful. I phoned my friend as early as I felt acceptable, pretty much at first light, and within an hour had Pageant back in my clutches. She heard me approaching before she saw me, and on recognising my voice, began to call excitedly, it broke my heart. I promised her that day I would never, ever leave her again.

Next chapter coming soon! Copyright Emma Raphael 2021.

-

Chapter Three - The Life of an Extraordinary Kestrel

1st March 2021

The third installment of my personal memoire. Scroll down for previous chapters.

Chapter Three – Fame

A bird so long lived in the public eye cannot escape eventual fame. Pageant is certainly one of our most photographed birds, the bird more guests have held and flown than any other, and the bird which has featured in the most advertising campaigns during my commercial career. When a press photographer arrives at an event and wants a quick shot, normally in some utterly unsuitable environment or in a questionable pose, it’s always the steadfast and highly tolerant birds which get selected for the job. Always Pageant! Stand here, look over there, hold this, raise her up there, put a Roman in front, a Medieval knight behind, a WWI soldier to the left and Queen Elizabeth I to the right – yep, that’s a job for good old Pageant. She has conducted every single falconry experience day throughout our career, she has appeared in posters, postcards, leaflets, booklets and all over the internet in online marketing and personal photos, and of course she has appeared on television. I have often visited a public toilet at a venue and closed the cubicle door to find my little bird staring back at me from an advertising board, I have sat in various hotel rooms around the country and seen her little face cheekily poking out from a tourist leaflet, I was even watching tv once and there she was helping to promote the many attractions at an iconic venue in the North. Impressive coverage for one so small and insignificant, certainly in comparison to her larger and more handsome cousins who so easily could have been selected instead. But if you need a job doing well you need a Pageant.

My favourite promotion was accidental and hilarious. We were due to present Medieval Falconry at Dover Castle, and so in the weeks before our visit, giant posters were dotted around the site advertising the upcoming event. The image selected by marketing was that of Pageant coming down to land on my glove, her wings arched back, and her legs extended forwards with open feet in preparation for landing, only Pageant and my glove were included in the frame, blown up to great size and detail so it filled the poster. A clever visitor to the castle, one of its thousands of international non-English speaking visitors, had interpreted the poster in their own unique way due to the scale of the image and the fact they probably did not understand its purpose. A dark-haired woman of Latin appearance stood at the bottom of the poster obscuring the image of my gloved hand with her body, her co-conspirator walked away a distance just great enough to include both her, in full profile, and the remainder of the poster above. The pose and perspective must have been tinkered with and perfected resulting in a bizarre image that was published on a certain social media platform. The image showed a giant-sized kestrel “hunting” a life-size woman with her feet perfectly positioned around the woman’s head, the woman had her arms raised as though she were being lifted from the ground with a terrified scream upon her face. It was clever and funny, although I suspect it did little to improve visitor attendance to our falconry event that weekend!

True fame only ever came to call for Pageant once and that was a starring role in a comedy television series in the early Noughties. We got the gig via a friend who worked occasionally at a television studio on Tottenham Court Road in London. The job description was ambiguous and so we didn’t really know how to prepare or which birds to take for the job, we knew it was static work, that it was indoors and involved training an actor for a sketch, but that was it. Driving into London 17 years ago without the help of satnav was a challenge but we arrived at a large concrete building with underground car park from which we had to unload our birds to the upstairs studio. We were given our own dressing room in which we quietly perched a selection of hooded falcons on a cadge frame; we expected that a traditional species of falconry bird in a brightly coloured plumed hood would be preferred for the shoot, something majestic looking, well behaved and large enough for the camera to easily pick up. It was decided by the assistant producer that it might be best if the actor chose the bird which they were most comfortable learning to handle. The actor would be sent along in due course. It was all a bit mysterious and secretive, or perhaps they thought we knew more than we did. Anyway, about half an hour later a petite blonde-haired lady was brought to meet us, she was the actor we were to train. Neither Mike or I recognised her. The larger falcons intimidated her a little so she selected the smallest, least heavy bird to hold upon her hand (imagining multiple takes and having to hold the bird for a good length of time). That bird was Pageant, the one we brought along as a spare, just in case, but supposed would be too plain and unimpressive to be of interest. We gave the actress some basic instruction in handling, she asked a plethora of questions about Pageant’s behaviour and quizzed us over falconry terminology, then she disappeared, and we twiddled our thumbs for a good hour waiting for something else to happen. All television work, we later came to understand, involved a lot of waiting around. Suddenly we were called to the studio; a large almost clinical room filled with unidentifiable technology and a separate chamber built in the middle draped on all sides with blackout cloth. We pushed through a slit in the cloth screen to find a small set inside built to recreate a radio station with mixing desk and microphone, it was a tiny set and purposefully cramped as if operating on a low budget. That is precisely what the scenario turned out to be. A familiar face entered the room, dutifully raised a hand to acknowledge us and then turned back out into the corridor, that face was the comedian and actor Steve Coogan. We were on the set of “I’m Alan Partridge” supposedly in the dingy local Norwich radio station from which his character worked when he wasn’t getting up to his wild antics or offending people on location reports. There was a farming or rural theme and Mr Partridge was due to interview a falconer, although clearly it was not going to be a smooth experience. We were handed a script so we could help the production team work out where to place the actress and how to manage the bird’s involvement. As I skimmed over the script, I noticed the words “chocolate mouse” and knew instantly this was not going to be a serious shoot!